Westerbork

|

| Camp Map |

The town of Westerbork is situated in the northeast of the Netherlands in the

province of Drenthe, about 130 km (80 miles) north of

Amsterdam. In a

resolution proposed by the Minister of Home Affairs and approved by the

Dutch cabinet on

13 February 1939, it was determined to construct a camp

"to house the refugees from Germany that live in this country". Opened on

9 October 1939, the costs of constructing the camp, amounting to 1.25 million

gulden, were charged to the Jewish Refugee Committee in the Netherlands.

When the Germans invaded the Netherlands in

May 1940, there were 750

refugees resident in the camp. Initially moved to

Leeuwarden, they were moved

back to Westerbork following the Dutch surrender. The camp came under the

control of the Ministry of Justice on

16 July 1940. Refugees from other camps

were subsequently moved to Westerbork, which by

1941 had a population of

1,100 in 200 small wooden houses. In the words of one commentator, it was a

site "about as inhospitable as could be, far from the civilized world in the

isolation of the Drenthe moorland, difficult to reach, with unpaved roads where

even the slightest shower would turn the sand to mud." The camp was also

plagued by hosts of flies during the summer months.

|

| Watchtower * |

|

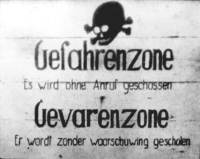

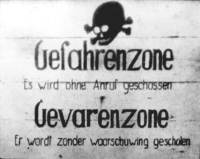

| Warning Sign |

At the

end of 1941, the Germans decided that Westerbork would become

a transit camp for Jews destined to be deported to the east. Measuring

500x500 m, the camp was surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. 24 large

wooden barracks were constructed. Eventually there were to be 107 such

barracks, each designed to hold 300 people. The costs of this building work

and of the camp's maintenance were to be financed from the proceeds of

confiscated Jewish property, an amount that was to exceed 10 million gulden

for

1942/43. During the first six months of

1942, 400 German

Jews were transferred to Westerbork from cities in the Netherlands from which Dutch

Jews had been evicted to

Amsterdam.

|

| Gemmeker |

On

1 July 1942, the

Befehlshaber der

Sicherheitspolizei und des SD took control of the camp, and SS troops arrived

to reinforce the Dutch military police guards.

Erich Deppner, a member of the

German administration in the Netherlands was appointed camp commandant,

to be succeeded by an SS officer,

Josef Hugo Dischner on

1 September 1942.

Both men having proved to be equally incompetent,

Albert Konrad Gemmeker

became commandant on

12 October 1942.

Gemmeker

left the day-to day

operation of the camp in the hands of German Jews, as had been the case from

inception, an arrangement which was not to change even when the majority of the

inmates were Dutch. The inmates rarely saw members of the SS other than

Gemmeker. On

13 July 1942, most of the

people who had lived in the camp, many of them for as long as two years, were dismissed from the

camp administration. Those dismissed included virtually everybody who was not deemed purely Jewish by

Nazi criteria. One day later all inmates born

between 1902 and 1925 were examined

on behalf of the

Arbeitseinsatz (Work Allocation Department).

Deppner explained: "Your labour is also needed for our victory."

|

| Gemmeker's House in 2006 |

The transfer of Jews from

Amsterdam to Westerbork began on the night of

14/15 July 1942, and the first transport left for

Auschwitz on the following day. In addition, on

15 July the

Dutch railroad company

Nederlandse Spoorwegen received an order for the construction

of a 5 km railroad into Camp Westerbork. The timetable for the trains, their size and

destination were determined by

Adolf Eichmann's lVB4 office.

Gemmeker left the

composition of the transports to the Jewish camp leadership (

Kampleiding). However,

certain inmates, such as those of foreign nationality or veteran servicemen were exempt

from transportation. Beginning on

2 February 1943, deportation trains left Westerbork on

Tuesdays, although there were periods in which no deportations took place. Initially transports

were in cattle wagons, although passenger cars were later also utilised.

Unlike other transit camps, Westerbork maintained a semi-permanent population who

remained in the camp for a considerable time, ran their own affairs and maintained a

near-normal life, especially in the periods when there were no deportations.

Elie Cohen, a doctor, was in Westerbork for 8 months before being sent to

Auschwitz. Whilst never

pleasant, conditions in the camp were far more bearable than in the transit camps in the

east, although the water supply was bad, and washing and sanitary facilities were inadequate.

The great majority of those who passed through the camp only stayed for a week or two before

boarding eastward bound trains, despite the

Kampleiding's attempts to save people from

deportation by providing them with jobs within the camp. For example, prisoners were

enrolled in the

Ordedienst, or in the

Fliegende Kolonne, a section who were responsible for

ensuring the transfer of deportees to the railway station in the nearby village of

Hooghalen, used before the railroad into the camp became operational.

Those Jews who had been caught in hiding within Holland were labelled "Convict Jews" and

were placed in a punishment block, Barrack 67. Unlike other inmates, they were not allowed

to keep their own clothes, but were forced to wear blue overalls and wooden clogs. Men

and women in the punishment block had their hair shaved, received no soap, less food than

other prisoners and were forced to work in the most arduous labour details.

|

| Arrival at Westerbork * |

|

| Departure from Westerbork * |

The camp administration consisted of twelve subdivisions. On

12 August 1943, one of the

subdivision heads,

Kurt Schlesinger, was appointed chief of the department

dealing with the vital main card index, from which the list of deportees was compiled. A

Joodsche

Ordedienst (Jewish Police Force), commanded by an Austrian,

Arthur Pisk, was also

created, with a maximum strength of 200 young men responsible for maintaining order

within the camp and at the transports. Westerbork took on many of the characteristics of a

small town. There was a hospital headed by

Dr F M Spanier, with 1,800 beds,

a maternity ward, laboratories, pharmacies, 120 doctors and a further 1,000 employees. Other facilities

included an old people's home, a huge modern kitchen, a school for children aged 6-14, an

orphanage and religious services. Workshops existed for stocking repair, tailoring, furniture

manufacturing, and bookbinding. There were divisions for locksmiths, decorators, bricklayers,

carpenters, veterinarians, opticians and gardeners. The camp included an electro-technical

division, a garage and boiler room, a sewage works, and a telephone exchange. In 1943,

when the "permanent" population was at its peak, 6,035 people were employed at the camp,

not all of whom were Jewish.

Although men and women were segregated at night, there was no restriction on their

movements during the day. Services within the camp included dental clinics, hairdressers,

photographers and a postal system. Various sporting activities were available, including

boxing, tug-of-war and gymnastics.

Gemmeker encouraged entertainment

activities – there was a cabaret, a choir and a ballet troupe. Toiletries, toys and plants could be purchased

from the camp warehouse. There were no shortages in the camp, since it was regularly

supplied by the Dutch administration and

Gemmeker had a fund at his disposal

appropriated from the Jewish property that had been confiscated.

In case it should be thought that this was an idyllic existence, it should be born in mind that

every inmate had the spectre of imminent death hanging over them. The railway line into the

camp had been completed in

November 1942 and allowed trains into the centre of the

compound. 101,525 of the 107,000 Dutch Jews deported to the east were interned at

Westerbork – 41,156 men, 45,867 women and 14,502 children. More than 95% of those

deported from the camp perished.

|

| Postcard from 1943 |

Fear of death dominated Westerbork and defined the behaviour of many of its inmates.

Although no detailed knowledge about the destination of the transports was known, the

prisoners were only too aware that the Germans were not planning anything that would

prove to the deportees benefit. In order to keep their names off the

transport lists, people

would do anything – "sacrifice their last hoarded halfpenny, their jewels, their clothes, their

food, or in the case of young girls, their bodies."

As each Tuesday approached, every inmate had to endure the trauma of possible deportation. A single example

of the horrific nature of these transports will suffice. An eyewitness,

Philip Mechanicus, a renowned journalist and author of a camp diary, recorded

on

10 June 1943:

"

About fifty children who were on the transports from

Vught have been admitted, dispersed in the isolation

barracks for the ill. They suffer from scarlet fever, measles, pneumonia, and mumps."

On

8 February 1944, a transport of more than 1,000 Jews was deported

from Westerbork to

Auschwitz-Birkenau. Among them were

268 of the camp's hospital patients, including children with scarlet fever and diphtheria.

Many of the sick were brought to the train on stretchers. On arrival at

Auschwitz-Birkenau , 142 men and 73 women were

admitted to the camp. The remaining 800 deportees, including all of the children, were gassed.

Mechanicus wrote:

"

Of all these bestial transports, perhaps this was the most fiendish."

Many of the sick were brought to the train on stretchers. On arrival at

Auschwitz-Birkenau, 142 men and 73 women were

admitted to the camp. The remaining 800 deportees, including all of the children, were gassed.

The final transport from the Netherlands to

Auschwitz

was on

3 September 1944.

Two days later the camp was crowded with members of the NSB (Dutch Nazi Party), who tried to flee

to Germany after false rumours of an invasion of the country by Allied forces ("Mad Tuesday").

The last transport to

Bergen-Belsen left on

15 September 1944. After this deportation, less than 1,000

inmates remained in

Westerbork.

Gemmeker remained an enigmatic figure. He rarely raised his voice

or dealt out punishments to the prisoners, and was said to be incorruptible. He took an interest in the camp's

entertainments and afterwards joked with the performers. Jewish gardeners cultivated

flowers for him and he was treated by Jewish doctors and dentists. Yet on Tuesdays he

stood quietly watching the trains depart for the east.

Gemmeker had a film made in

Westerbork which was to show everything, good and bad, of the camp's daily life. Scenes from the film appear frequently

in Shoah-related documentaries. One particularly haunting image from the film, that of a 9 year-old girl staring

from the doorway of a cattle wagon, has become synonymous with the Holocaust. The girl, who was in fact not Jewish,

but Roma, was named

Settela Steinbach. She perished in

Auschwitz-Birkenau.

On

12 April 1945, as allied forces approached Westerbork,

Gemmeker handed the camp

over to

Schlesinger. On that day, there were 876 prisoners in the camp,

of whom 569 were Dutch. The remainder were of various nationalities, or stateless.

Gemmeker was sentenced

to 10 years imprisonment by a post-war Dutch court. Extenuating circumstances were taken

into account in arriving at the sentence, in that "in general he had treated Jews decently

during their stay in the camp."

As with some other transit camps, Westerbork had its own

currency.

See

Westerbork today!

Vught

|

| Camp Map |

|

| Chmielewski |

Originally established as a

Schutzhaftlager for Dutch political prisoners, the camp at

Vught, near the southern city of

`s Hertogenbosch, capital of the province of Noord-Brabant,

was taken over in

late 1942 by the

WVHA (Wirtschaftsverwaltungshauptamt - SS

Economic-Administrative Main Office). Now designated

KL Herzogenbusch, the camp

became part concentration camp housing political prisoners, and part transit camp for Jews.

Karl Chmielewski was appointed camp commandant.

Chmielewski had previously served

at

KL Mauthausen/Gusen, and on his appointment transferred 80

Kapos from that camp to Vught. However, in contrast to

Mauthausen, there were strict instructions to refrain from

mistreating prisoners at Vught. Experience at

Westerbork had

shown that deportations were more easily managed if cruelty was avoided.

The camp, measuring 500x200 m, consisted of 36 living and 23 working barracks.

A double barbed-wire fence with a ditch between them surrounded the camp. Watchtowers

were placed every 50 m around the perimeter. Situated outside the camp boundary

were the SS barracks, an execution area and a

Philips industrial plant.

|

| Grünewald |

|

| Hüttig |

The first Jewish prisoners arrived in Vught in

January 1943 and by

May 1943 their number

had grown to 8,684. There were also non-Jewish prisoners in the

Schutzhaftlager section.

Conditions in the camp were very poor, although some improvement occurred following a

visit by

David Cohen of the

Joodsche Raad. From

April 1943, a number

of male prisoners were sent to work outside the camp, although most inmates were employed

within the camp in the manufacture of clothing and furs. The most desirable workplace

was that of the

Philips company, where 1,200 prisoners were employed. The company

insisted that its Jewish workers should enjoy decent conditions, including a hot meal every

day and also not be subject to deportation. Dr

Arthur Lehmann was appointed head of

the Jewish administration in the camp in

October 1943. He did his best to care for the

prisoners and was very popular with them. For a time religious and cultural activities had

taken place and a school had functioned, but circumstances changed for the worse with the

appointment of

Chmielewski's successor,

Adam Grünewald in

October 1943.

Grünewald was removed in turn in

January 1944

because of the excessive punishments

he had meted out, and was succeeded by

Hans Hüttig.

|

| Childrens Memorial |

A

proclamation was issued by the Vught

Kampleiding on

5 June 1943.

Two transports were to be sent to "a special children's camp". In accordance with the terms of the

proclamation, all children up to the age of 3 were to be accompanied by their mothers

and those aged between 3 and 16 by one of their parents. The "special children's camp" was

Sobibor. The first train, containing 1,750 victims, many of them unaccompanied sick

children, arrived at

Westerbork on

7 June 1943.

The second arrived a day later. 1,300 tired, filthy people were transferred, "amid snarling and shouting,

beating and pummelling" from the dirty freight cars in which they had arrived to the dirty freight cars that would

transport them to

Sobibor.

With the exception of two transports which were directed to

Auschwitz, all transports from

Vught were routed via

Westerbork. The first of these transports to

Westerbork had left at the

end of

January 1943, shortly after the transit camp at Vught had been established. The

camp's population peaked in

May 1943 but steadily declined until

3 June 1944, when the camp was liquidated. The last group to be transported from Vught,

on

3 June 1944, was made up of 517

Philips' employees, the company having

failed to save them, but even in

Auschwitz this group received preferential

treatment, being employed by

Telefunken under an agreement made between

Telefunken and

Philips. Nonetheless, most of the men in this party perished. 160 of the group survived;

two-thirds were women and 9 were children.

Today the former camp is part of the army barracks of the Dutch Royal Engineers.

Barneveld

A third transit camp was established at Barneveld in the province of Gelderland.

Between

December 1942 and September 1943, some 700 Jews were housed in a castle,

"De Schaffelaar", and in a former relief camp for unemployed people, "De Biezen."

These were mainly socially or culturally prominent Jews – academics, lawyers, artists,

and the like. The inmates led a relatively privileged existence. They were allowed to bring

their own furniture with them, were not required to perform hard labour and were adequately

supplied with rations. However, overcrowding and the resultant lack of privacy remained

a problem. The camp, commanded by a Dutch former army officer, had 6 "controleurs"

who served as guards. The staff were not paid by the government, but from a camp fund

financed by the inmates.

The camp was closed on

29 September 1943. About 680 prisoners were transferred to

Westerbork, of whom 22 managed to escape in transit. The inmates from Barneveld

continued to enjoy their privileged status in

Westerbork. None of them were transported to

Auschwitz and when deportation did occur, they were sent in a group to

Terezin (Theresienstadt).

Other Camps

There were other camps in which Jews were interned, normally prior to being transferred

to either

Westerbork or

Vught. These were situated at

Schoorl in the province of Noord-Holland,

Amersfoort in the province of Utrecht and

Ommen in the province of Overijssel. More properly

categorized as concentration rather than transit camps, they were not primarily intended for the

incarceration of Jews, although some Jews were temporarily held there. The regime at these

camps was much harsher than that of

Vught and especially that of

Westerbork.

Elie Cohen,

who was held for a time at

Amersfoort, said that "transfer from

Amersfoort to

Westerbork was like going from hell to heaven."

Photos: GFH

*

Vught camp map: Nationaal Monument Kamp Vught

Sources:

Gutman, Israel, ed.

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990

Hilberg, Raul.

The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003

Gilbert, Martin.

The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy, William Collins Sons & Co. Limited, London, 1986

Lee, Carol Ann.

Roses from the Earth: The Biography of Anne Frank, Penguin Books, London, 2000

Gill, Anton.

The Journey Back from Hell, Grafton Books, London 1988.

Dr. J. Presser,

Ondergang, de vervolging en verdelging van het Nederlandse

Jodendom 1940-1945, Staatsuitgeverij, ‘s-Gravenhage 1965

J.C.H. Blom e.a..

Geschiedenis van de Joden in Nederland, Olympus, 1995

Dr. L. de Jong, Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie.

Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede

Wereldoorlog, deel 8, Gevangenen en gedeporteerden, Martinus Nijhoff, 's-Gravenhage,1978

© ARC (http://www.deathcamps.org) 2005