On

5 January 1944,

Odilo Globocnik wrote to

Heinrich Himmler from

Trieste, setting out

details of the economic plunder of

Aktion Reinhard.

It followed an earlier report that

Globocnik had submitted on

4 November 1943.

In fine detail,

Globocnik calculated the gross yield to Germany of the murder

of some 2 million Jews at a sum in excess of 178 million

Reichsmark, then equal to US$71 million. The equivalent

value today (

2004) would be approximately US$760 million. Impressive though this

figure is, it represents no more than a fraction of the true extent of the larceny involved.

In the second of his letters,

Globocnik was at pains to stress the accuracy of his

bookkeeping, since "

a certain odium still rests upon me to the effect that in all

economic matters I do not

maintain the necessary order."

Globocnik was right to be concerned; after

all, he had been dismissed as

Gauleiter of

Wien in

January 1939 because of illegal currency dealings.

Doubtless, his reputation went before him, and he could hardly have been comforted by the web of corruption within

the SS revealed by the investigations of SS Judge

Konrad Morgen in

1943. Yet could

Himmler have really believed that

Globocnik’s financial statements were accurate? On

Globocnik’s own admission, "

What is remarkable about

the accounting is that no hard and fast basis for the amount collected existed, as the collection

of the assets was carried out under

orders and only the decency and honesty, as well as the surveillance, of the SS men used for this purpose could

guarantee a complete delivery." In other words, a financial free-for-all had prevailed. There was no real

supervision in place, no adequate system of checking and controlling the vast sums involved. But this was hardly

surprising. An ideology based upon theft and murder produces thieves and murderers, and whilst economic considerations

were never allowed to override the racial imperative, the two went hand-in-hand in the National Socialist state.

Theft, larceny and extortion could be characterised at two levels – the governmental, "legal" in the sense that

any act of government can be legalised, and personal, "legal" in that it was authorised (sometimes tacitly) by

government and "illegal", as practised by countless thousands of German civilians, members of the armed forces,

SS and police. And, as the opportunity arose, by many citizens of the countries occupied by, or allied to, Germany.

Although it can be said that

Aktion Reinhard entered its main extermination phase with the commencement

of killing operations at

Belzec in

March 1942, and concluded with

"

Aktion Erntefest" in

November 1943,

the periods preceding commencement and following conclusion are important for an understanding of the

economic development and importance of Nazi economic policy. In turn, it is necessary to examine the way in which

these policies were formulated, and for that a brief overview of the methods adopted in the

Reich and the

manner in which these were varied in the occupied territories is required.

The template for the economic exploitation and expropriation of Jewish property was laid down in the early

stages of the Third

Reich’s existence. "The Law for the Reestablishment of the Professional Civil Service" was

enacted by decree on

7 April 1933, little more than two months after the Nazi’s

seizure of power. At a stroke,

all "non-Aryan" members of the civil service were compelled to retire. It was the first in a series of such decrees.

Over the coming months and years, Jews were barred from practising law and medicine, dismissed from the

armed forces, prohibited from engaging in journalism and from the arts. No profession was left open to them.

Employers in every kind of undertaking were encouraged to dismiss their Jewish workforce. The conditions of

dismissal for employees became steadily worse, and the later a Jew was removed, the less his compensation

or pension. Ultimately, it became very difficult for Jews to remain in any kind of employment.

On

14 June 1938, the Ministry of the Interior published a decree defining a

"Jewish enterprise". This was the initial

move in the compulsory transfer of Jewish businesses into German hands. Previously, a Jewish business

could be either liquidated, and disappear, or be "Aryanized", and purchased by Germans. "Aryanization"

was in turn either voluntary (until

November 1938), or thereafter, compulsory.

The term "voluntary" was a misnomer,

since there was no open market negotiation of a business’ value. Jewish enterprises were purchased at heavily

discounted prices, encouraged by a series of government measures calculated to drive values down. The

introduction of compulsory "Aryanization" was effected through "trustees", appointed by the Ministry of Economics.

In many cases, virtually no compensation was paid for the acquisition of Jewish assets. The city of

Fürth,

for example, obtained 100,000

Reichsmark of Jewish communal property for 100

Reichsmark. The process was

simple; the "trustee" paid as little as possible and sold on to a German buyer for as much as possible. The difference

went to the

Reich, at least in theory. In practice, German purchasers were reluctant to pay the real market

value of Jewish enterprises, and it became necessary for the government to introduce an "equalization" tax in order

to collect their share of the spoils. In general, the purchaser of a Jewish business rarely paid more than 75% of its

value and frequently paid less than 50%. The profit to the business sector from this state controlled theft can be

calculated in billions of

Reichsmark.

But the state had acquired little direct financial benefit from this policy. Its windfall was to come from a penal

system of taxation. This comprised two property taxes – the so-called "

Reich Flight Tax" and the so-called

"Atonement Payment". The "

Reich Flight Tax" had, in fact been in existence since

December 1931, more than one

year before

Hitler attained power, and was intended to extract a proportion of the

value of the assets of those emigrating from Germany. By combining their enthusiasm for the emigration of Jews with a

lowering of the tax threshold, during their brief tenure in office, the Nazis obtained in the region of 900 million

Reichsmark from Jewish emigrants.

The "Atonement Payment" arose in the wake of the assassination of

Ernst vom Rath

by

Herschel Grynszpan and the subsequent

Reichskristallnacht of

9 - 10 November 1938. The Jewish community were "fined" an amount which eventually

amounted to 1.126 billion

Reichsmark

by way of reparation, payable in four instalments. The combined proceeds of the two taxes, an amount in excess of 2

billion

Reichsmark, was an essential contribution towards an economy that was heading for meltdown because of

excessive spending on armaments. The "Atonement Payment" also set the precedent for future German methods of extortion

in the occupied countries.

By

1939, the remaining Jewish community of Germany, now half its former

size because of emigration,

was impoverished. Those Jews who were still in employment had their wages reduced and their taxes increased.

What could be purchased with the little that was left to them was severely restricted by the imposition of rationing,

as the Germany economy entered a war footing. Rations for Jews were fixed at a level lower than that of the

general population. Together with a host of other restrictions, even the hours during which Jews were allowed

to shop were limited.

The economic exploitation of the

Reich Jews had maintained at least a façade of legality. With the invasion

of Poland, that façade was stripped away. The Jewish community of Germany had significant amounts

of capital, but were relatively few in number. In Poland, that position was precisely reversed. But that did

not mean that the opportunity for theft was to be overlooked. It had taken six years to pauperise the Jews

of Germany. The same result was achieved with Poland's Jews in a matter of weeks. Robbery of Polish

Jews and looting of their property became the norm. In every town and village, Jews were forced to hand

over not merely gold, currency and other valuables, but virtually anything consumable, including furniture

and clothing. Even items such as birdcages, door handles and hot-water bottles were looted. Any excuse,

or none at all, became the pretext for extortion. In the

Warsaw Ghetto,

Adam Czerniakow wrote in his diary:

"

It is raining. Fortunately that does not involve charges on the community."

Czerniakow's irony is understandable; the Jews of

Warsaw had already been forced to pay for the erection of the wall that

imprisoned them. Often, hostages were taken to ensure payment of Nazi demands.

|

| Wloclawek Synagogue |

One example among many will suffice: on

Yom Kippur 1939, the Germans burnt down two

synagogues in the town of

Wloclawek. The fire spread to neighbouring houses.

The Nazis took 26 men into custody, forcing them

to sign a confession that they had started the fire. The men were then arrested, and told they would be

released on payment of a ransom of 250,000 Zloty. The Jewish population raised the money.

Shortly after, a new fine of 500,000 Zloty was imposed on the Jewish population for supposedly not

obeying the ban on their using the pavement.

Shortly after the entry of the German army into every town, soldiers and members of the civil

administration plundered Jewish homes. In many cases the local non-Jewish population helped the

Germans in searching for wealthy Jewish houses and shops. At the beginning of the Nazi occupation,

some confiscations of Jewish property were organised officially, but in many cases this looting was

undertaken on the private initiative of local Germans.

Ida Gliksztajn,

a survivor from the

Lublin Ghetto described her experiences:

"

On one occasion, two German soldiers and an official from the town hall arrived

to take pillow-cases

and sheets. It was at the beginning of the occupation and they gave us a receipt for about four

pieces of linen. Another time, several soldiers came to take the table, sofa bed and chandelier.

One Friday morning, two civilians and a man in uniform visited us. They were looking for

counterpanes but instead they took away a violin and a camera. On yet another occasion, the

Germans searched for gold. The search lasted the whole day. They ordered all of the women

in the house to undress themselves. We were not spared mockery and vulgar remarks."

Extortion on a grand scale took place throughout Poland. How much of these "fines" found their

way into the coffers of government is questionable. It was for good reason that

Hans Franks

Generalgouvernement (that part of Eastern Poland

not incorporated into the

Reich) was known as the "Gangster

Gau". A similar pattern was to emerge in

other territories occupied by the Nazis following the invasion of the former Soviet Union.

By

November 1939, all Jewish bank accounts in the

Generalgouvernement had

been blocked. Jews were only permitted to withdraw 250 zloty per week from these blocked accounts, or a larger

amount if needed for business purposes. At the same time, they had to deposit all cash reserves in

excess of 2,000 Zloty into the blocked account. On

24 January 1940, a decree

was issued requiring

the Jews of the

Generalgouvernement to register all property, including clothes, cooking utensils,

furniture and jewellery. Simultaneously, all Jewish property was subject to confiscation. Jewish

businesses were rapidly liquidated. In less than two years, 112,000 enterprises were reduced to 3,000.

The raw materials and finished goods of these liquidated firms provided a handsome windfall for the

Germans. The businesses themselves were sold to

Volksdeutsche for the price of the machinery

and inventory only. Poles ejected from the proposed ghetto areas were re-housed in the vacated

Jewish apartments, as were resettled

Volksdeutsche. The better Jewish homes were plundered

for furniture.

Even the creation of the ghettos themselves had a partial economic consideration behind it.

Ghettos were a much cheaper proposition than concentration camps. There was no need to

construct barracks, provide sanitation or light and heat. Guarding them was much simpler, and

cramming the Jews into a designated area facilitated robbery. In the

Warthegau,

Arthur Greiser said of the ghettos:

"

The Jews will remain there until what they have amassed to exchange for food is returned."

This was the essential economic thinking

behind the ghettos - press the Jews into a restricted area, steal from them what can be stolen,

forbid them to practise their professions or engage in gainful employment, maintain rations at starvation

level, and before they eventually die, they will be forced to exchange whatever remains of their wealth for

food. Which, to a great extent, is what happened. Typically, a ghetto resident would make up the deficit

in his or her weekly budget by selling some of their remaining personal possessions. There was

some trade between Jews, but in the main, a system of barter of goods for food with their fellow

non-Jewish citizens occurred. Since this was very much a buyer’s market, there was often no correlation

between the true value of these articles and the price the seller received. It has been estimated that

during the occupation, wages in the

Generalgouvernement rose 100%. In contrast, compared to

September 1939, the price of food in

Warsaw

markets had increased twenty-seven fold by

May 1942.

Incarceration in ghettos also opened up new possibilities for self-enrichment. The only legal source

of food was that purchased by the

Judenräte with funds collected from the ghetto population.

The food was supplied by the

Transferstelle,

Ghettoverwaltung (German administrative authorities)

or by municipal administration. The

Judenräte would pay for a specified quantity of food. Frequently,

a lower quantity was delivered. Moreover, if delivered, the food was usually of the lowest possible

quality, often inedible. Men like

Hans Biebow in

Lodz and many like him in

other ghettos accumulated great wealth from such transactions. In addition, only the smuggling of

food into the ghetto made existence possible at all. The opportunity for the bribery and corruption

of officials, from the heads of ghetto administrations to guards at ghetto gates, were endless, and fully

exploited by those in authority.

Initially, compulsory Jewish labour was only utilised for the most menial and strenuous work –

clearing rubble, draining swamps, building fortifications and the like. But in

mid-1940,

a shortage of skilled manpower forced the Germans to the realisation that the Jews could be put to more

productive use. In the wake of the occupying army, a host of would-be entrepreneurs had descended

on Poland. Men such as

Oskar Schindler and

Walter Toebbens arrived in much the same manner that carpetbaggers

had swooped on the Confederate States in the wake of the American Civil War. The pickings were rich.

When paid at all, salaries were miniscule. In

Warsaw, after deductions, an average

workshop employee

received 3 - 5 Zloty per day – not enough to buy half a loaf of bread. In many ghettos and factories,

even this tiny salary was not paid. The Jews became, quite literally, slave workers. They were "owned"

by the SS, who received an agreed daily rate from the industrialists for every labourer provided to them.

The workers’ reward was a midday plate of thin soup and a slice of bread. Given an insatiable demand

by the

Wehrmacht and others, together with minimum costs, even employers such as

Oskar Schindler, whose pre- and post-war activities hardly

suggest an acute business brain, could hardly fail to turn a profit.

Many German industrialists and merchants created large enterprises utilising Jewish labour. Some

German companies even controlled monopolies in the

Generalgouvernement for certain products,

and most of their workers were Jewish. A good example of this was

Viktor Kremin's

company, which confiscated all Jewish enterprises in the districts of

Radom, Lublin

and Galicia concerned

with the gathering of glass, iron, paper and rags.

Kremin not only seized the

buildings and stores of these entities, but also availed himself of the former Jewish owners together with their

workers. Because the gathering of industrial waste was important for the war economy,

Kremin's workers were actually temporarily saved at the time of the first

wave of deportations to the death camps.

At the same time, the SS themselves entered the market as major exploiters of Jewish labour.

Oswald Pohl, a former naval paymaster, set up a chain of SS

enterprises in labour and concentration camps. The organisation he controlled eventually evolved

into the

Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt

(

WVHA). Initially consisting of two main companies,

German Earth and Stone Works (

Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke / DEST) and German Equipment

Works (

Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke / DAW), the organisation expanded to encompass divisions

involved in agriculture, food production, textiles and leather and other activities. One of the most

important of these was the production of munitions. Whereas in

1940, the Jews had

been considered

incapable of productive labour, by

April 1944 more than 28,000 of them were employed in the

armaments industry alone – and this after the slaughter of

Aktion Reinhard had ceased. At its height,

the

WVHA had a work force of more than 500,000 concentration camp prisoners at its disposal, making

Pohl one of the most powerful men in the SS. It was

Pohl who masterminded the economic aspects of

Aktion Reinhard,

organizing the disposal of the personal possessions of the murdered Jews. For the utilization of

Jewish labour was only an intermediary step prior to their murder. In

Pohl's

words: "

Employable Jews who are migrating to the East will have to interrupt

their journey and work in war industry."

Indeed, the use of slave labour was itself part of the extermination process, for the SS were hardly

caring employers, and working and living conditions in the camps and in the industries they supplied,

were uniformly dreadful.

On

1 December 1942,

Himmler wrote to

Pohl, stating that he had looked at the machinery and equipment in the

Warsaw Ghetto following the deportation of most of that city's Jews to

Treblinka. According to

Himmler, this equipment represented a windfall worth "hundreds of millions",

even though the majority of the machinery was actually private property. Utilising this equipment,

together with that recovered from the

Bialystok Ghetto on

12 March 1943,

the SS formed a new

company,

Ostindustrie GmbH (Osti), operating within the framework of the

WVHA. At its peak,

Osti employed thousands of Jews in various enterprises in

Dorohucza,

Lublin,

Radom,

Lviv (Lwow) and

Trawniki. In the various work camps of the

Lublin district and in

Majdanek alone, there were about

50.000 Jewish prisoners who worked for the

Osti factories.

Globocnik,

who was the head of

Osti, even wanted to transfer Jews from the

Lodz Ghetto to the

Lublin

district and to

use them as workers for his company. Because of the refusal of

Biebow

to cooperate and the liquidation of the Jewish work camps in the

Lublin district,

this idea was never pursued. The

Osti enterprise was short-lived. On

3 November 1943,

most of its workforce was shot in the

Aktion Erntefest. It was a classic example of racial policy

taking precedence over economic necessity.

|

| Dental Gold |

|

| Chopin Street Depot |

The city of

Lublin was the nerve centre of

Aktion Reinhard. It was from here

that the operation was organised and administered, and to here that the vast bulk of the proceeds of mass murder

were sent.

Globocnik issued instructions for a central register of all property

confiscated in the camps to be set up.

Georg Wippern was placed in charge of valuables and

Hermann Höfle was made responsible

for the sorting of clothing. At camps established at the

Airfield Camp (

Flugplatz-Lager),

and

Lipowa Street (

Lipowa Straße),

at the depot on

Chopin Street and elsewhere in the city, as well at

Majdanek concentration camp in

the city's suburbs, thousands of Jews laboured in conditions of the utmost harshness and brutality to

sort, repair, disinfect and pack everything from underwear and bedding to watches and currency.

Nothing was to be omitted.

Women's hair, shaved at the entrance to the

gas chambers, was sent

to Germany to be woven into felt stockings for railroad workers, socks for submarine crews, and perhaps

insulation material for German submarines. Dental gold, extracted from the mouths of gassed Jews, was melted and

delivered to the German

Reichsbank.

|

| Reichsbank |

In addition to the

Airfield Camp and

Chopin

Street,

there were two other localities in

Lublin where

Jewish prisoners sorted the property belonging to the victims of

Aktion Reinhard. One of these was the

SS-Standortverwaltung (SS Garrison Administration) on

Chmielna Street.

The main store for valuables and money plundered in the death camps and at

Majdanek

was located in the building of the former ocular hospital at this address. Small groups of Jewish workers, mainly

jewellers from the

Lublin Ghetto and bankers deported from

Terezin (

Theresienstadt), catalogued the

valuables and counted the money. Money and

valuables arrived at the

SS-Standortverwaltung without special documentation and it was only there

that lists of the gold and currency were prepared, prior to sending them to the

Reichsbank. It was

quite normal for the SS men who worked there to steal the best items for themselves. At the

beginning of 1943, when

Himmler visited

Lublin, a special exhibition

of jewellery was organised in the

SS-Standortverwaltung. According to the only survivor from the Jewish

commando that worked there,

Ignacy Wieniarz,

"

it was the best and biggest exhibition of Jewish jewellery in the whole of occupied

Europe at that time."

The other place connected with the plunder and sorting of Jewish property in

Lublin

was the work camp at the

Sports Field, (

Sportplatz),

and especially the former cosmetic factory owned before the war by the Jewish industrialist from

Lublin,

Roman Keindl.

The former owner worked there too, but as the

Lagerkapo. In his factory, which was under the supervision of

SS-Standortarzt (Garrison Doctor)

Sieckel, the cosmetics, medical equipment

and medicines which had been stolen from Jewish victims were separated and itemised.

Some idea of the thoroughness of this plunder of the murdered can be gleaned from an order issued by

August Frank of the

WVHA to the

Aktion Reinhard headquarters

on

26 September 1942. An edited version of these guidelines is worthy of reproduction:

1. All German currency will be deposited in the

WVHA account at the

Reichsbank.

2. Foreign currency, precious metals, diamonds, precious stones, pearls, gold teeth and pieces of

gold will be transferred to the

WVHA for deposit in the

Reichsbank.

3. Watches, fountain pens, lead pencils, shaving utensils, pen knives, scissors,

pocket flashlights and purses will be transferred to the workshops of the

WVHA for cleaning

and repair and from there will be transferred to SS troops for sale.

4. Men's clothing and underwear, including shoes, will be sorted and checked.

Whatever cannot be used by concentration camp prisoners and items of special value

will be kept for SS-troops; the rest will be transferred to

VoMi (

Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle /

Department for

Volksdeutsche, a section of the SS responsible for aiding Ethnic Germans in occupied countries).

5. Women's underwear and clothing will be sold to the

VoMi, except for pure silk underwear

(men's or women's), which will be sent directly to the Economic Ministry.

6. Feather-bedding, blankets, umbrellas, baby carriages, handbags, leather belts, baskets,

pipes, sunglasses, mirrors, briefcases and material will be transferred to

VoMi.

7. Bedding, like sheets and pillowcases, as well as towels and tablecloths will be sold to

VoMi.

8. All types of eyeglasses will be forwarded for the use of the Medical Authority. Glasses with

gold frames will be transferred without the lenses along with the precious metals.

9. All types of expensive furs will be transferred to the

WVHA. Furs of lesser quality will

be transferred to the

Waffen-SS clothing workshops in

Ravensbrück

near

Fürstenberg.

10. All articles mentioned in 4,5,6, of little or no value will be transferred to the

WVHA for the

use of the Economic Ministry. With regard to articles not specified above, the chief

of the

WVHA should be consulted as to the use to be made of them.

11. Check that all Jewish stars have been removed from all clothing before transfer.

Carefully check whether all hidden and sewn-in valuables have been removed from

all articles to be transferred.

The looting began in the camps themselves. Initially, the handful of deportees, selected from

arriving transports for work within the camps, were routinely murdered after a few days at most,

to be replaced by new arrivals. It quickly became apparent that this constant renewal of the

workforce caused disruption to and a slowing of the extermination process.

Franz Stangl, then commandant of

Sobibor, and ever the efficient

policeman, realised that a more permanent body of working prisoners was needed. To be sure,

murder of the workforce remained an ever present in all of the camps, and the ultimate fate of

the workers was never in doubt, but now it was at least possible to survive for more than a day

or two. Ironically, it is thanks to

Stangl that a handful of the working

prisoners were to live long enough to escape from

Sobibor and

Treblinka and provide us with eyewitness testimony of their horrors.

Amongst others,

Yankel Wiernik survived for a year in

Treblinka,

Richard Glazar

for ten months. In

Sobibor,

Toivi Blatt

endured captivity for six months. Of

Belzec, we have

the testimony of

Rudolf Reder, one of only two survivors of that camp,

and the sole provider of written survivor evidence,

Reder, who

was in

Belzec for approximately 4 months.

The first camp in which these changes regarding the workforce occurred, was

Sobibor, in

May or June 1942, to be followed

shortly thereafter by

Belzec and finally by

Treblinka in

September 1942 on

Stangl's appointment as commandant.

The prisoners were organised into small work groups with specific responsibilities. The

Goldjuden

("Goldjews"), about 20 in number and mainly comprising jewellers, watchmakers and bank

clerks, were responsible for receiving and sorting money, gold, foreign currency and other

valuables. The

Friseure (Hair Cutters) between 10 and 20 mainly former barbers, cut the hair

of the women at the entrance to the gas chambers. The largest group, numbering 80-120,

was the

Lumpenkommando (Sorting Team for Clothing and Belongings). Their job was to

collect and sort the victims' clothing and belongings and load them onto freight cars.

The clothing was carefully examined for hidden documents and valuables, and all markings,

such as the yellow star, which might identify the now deceased owner as a Jew, removed. There

were several other groups concerned with the collection and sorting of goods, as well as the

cleaning of the gas chambers, the disposal of bodies and other activities not directly connected to

the gathering of plunder.

The value of that plunder was immense.

Stangl himself described

how, on arrival at

Treblinka, where under

Irmfried

Eberl's command the camp regime had completely broken down:

"

I stepped knee-deep into money; I didn't know which

way to turn, where to go. I waded in notes, currency, precious stones, jewellery, clothes.

They were everywhere, strewn all over the square."

Samuel Willenberg, working in the sorting area at

Treblinka, opened sewn-up folds in clothing to remove gold coins,

roubles, dollars and diamonds.

Richard Glazar, another

prisoner at

Treblinka, tells of poles driven into the ground of the sorting yard

bearing signs reading "Cotton", "Silk", "Wool" and "Rags". Huge piles were stacked up beneath each sign.

Glazar commented:

"

It is all but impossible to imagine what can be found among the last things packed by

thousands and thousands. This is a huge junk store where everything can be found – except life."

Another

Treblinka inmate,

Alexander Kudlik, relates how he spent about six months going

through nothing but gold pens for ten hours a day. At

Belzec,

Rudolf Reder

described how a group of 8 dentists opened the mouths of corpses and extracted gold teeth. The

gold, money and valuables were sent to

Chopin Street in

Lublin. In

Sobibor,

Thomas Toivi Blatt, like prisoners in all of the camps, purloined money

and valuables to keep as a reserve in the event of escape and to barter for food with the Ukrainian guards.

The price of a sausage was a gold watch.

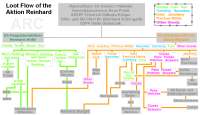

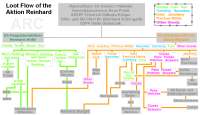

|

| Loot Flow Chart |

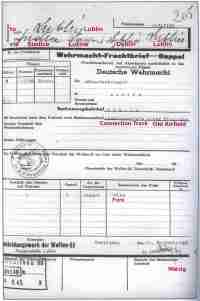

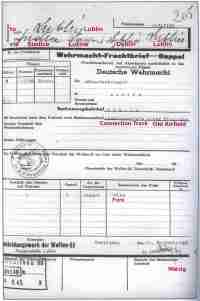

|

| Pohl Letter |

A precise system was drawn up in

Berlin for the disposal of the money and

valuables. Coins were retained by the Precious Metals Division of the

Reichsbank. Stocks, bonds and bankbooks

were sent to the Securities Division of the bank. Dental gold was sent to the Prussian State

Mint for melting. Jewellery was delivered to the

Berlin Pawnshop. The proceeds

of all of these activities were deposited at the Treasury, where they were credited to the Finance Ministry in

a special account in the fictitious name of "Max Heiliger". Withdrawals from this account were

included in the national budget.

The wealth of nations passed through these tiny camps in Eastern Poland.

Shmuel Rajzman testified how he and others kept count of the transports

leaving

Treblinka with the possessions of the victims. These included 248 railway

cars of clothing, 100 cars

of shoes, 22 cars of material, 260 cars of bedding, about 450 cars with various articles and household goods,

and hundreds more cars with rags; in total, about 1,500 cars full of the effects of murdered Jews.

Rajzman also told of how he had been informed by a Jew

responsible for packing valuables, that over 14,000 carats of diamonds alone had been sent from

Treblinka.

Abraham Lindwaser, also incarcerated in

Treblinka, reported that

during the period that transports arrived, an average of two suitcases, each containing 18 kg

of gold, were sent from the camp each week.

Treblinka provided the highest yield

of booty and the

most detailed witness testimony, but there is no doubt that the proceeds of annihilation were

proportionate to the number of victims. If the pillage was less at

Belzec and

Sobibor, this was solely due to the lower numbers murdered there.

|

| Furs to Old Airfield |

All the trains with clothing were sent to the

Airfield Camp in

Lublin, where 500 - 700 Jewish

prisoners worked, the majority of them women. An initial sorting had taken place in the

camps. Now the clothes were disinfected and further sorted first into men's, women's and

children's items, then into outer and under clothing and footwear. Finally, the neatly packaged

effects were loaded onto trains once more and distributed in accordance with

Frank's instructions of

26 September 1942

(reproduced above).

Pohl issued a report on

6 February 1943,

detailing the textile materials forwarded from

Auschwitz and from

Aktion Reinhard. Since the report dealt with

goods transferred during

1942, it is apparent that the bulk of the items had come from the

Aktion Reinhard camps. The

Reich Economic Ministry had received 262,000 complete men's

and women's outfits, over 2.7 million kg of rags, 270,000 kg of bed feathers and 3,000 kg of

women's hair.

VoMi and other organizations were in receipt of a further 255 freight cars of clothing and

textiles.

Franz Suchomel, in charge of the

Goldjuden in

Treblinka, related how, during

Eberl's tenure of office as commandant of

Treblinka, a messenger had

arrived from the

Führer's Chancellery. The messenger carried instructions from

Werner Blankenburg of the euthanasia programme, to collect one

million

Reichsmark. A suitcase was duly filled and handed over. No questions were asked. The messenger

returned to

Berlin. It was only one of countless cases of pilfering by the SS at

every level, as well as

by their Ukrainian cohorts and anybody else unscrupulous and immoral enough to thrive on the misery of others.

Stangl believed that his immediate superior,

Christian Wirth, was bypassing

Aktion Reinhard headquarters

and transferring money and valuables direct from

Treblinka to

Berlin. Since, despite being nominally under

Globocnik's command,

Wirth

took instructions directly from

Viktor Brack in the

Führer's

Chancellery or from

Brack's deputy,

Blankenburg.

Stangl was probably correct in his suspicions. If so, it is likely that no

records of these particular transactions were kept.

When returning to Germany on leave, the SS would take suitcases and parcels full of Jewish belongings.

Abraham Krzepicki, a prisoner in

Treblinka,

reported how both, German and Ukrainian camp staff, had so much money he considered that they all

became millionaires. The Ukrainian guards stole money and valuables directly from the

Jews as they were brought to the camps. Sometimes they would burst into the barracks

where the

Goldjuden worked and steal whatever they could take. There was a thriving trade

between the Ukrainian guards and the local population. Money and valuables flooded into the

regions surrounding

Treblinka, Sobibor and Belzec, attracting speculators by the

score. Prostitutes arrived from

Warsaw and elsewhere to service the Ukrainians.

Jerzy Krolikowski, a Polish engineer who worked in the vicinity of

Treblinka wrote:

"

The poor areas of Podlassia

overflowed with gold, and riffraff from all over the country came there to get rich quickly and easily…

At first (the Ukrainians) were not aware of the real value of articles, and one could buy all kind

of things for next to nothing. Men's watches were sold literally for pennies, and local farmers

kept dozens of them in egg baskets to offer them for sale."

The greatest benefactors of this larceny,

of course, were the higher officers of the SS. Nobody will ever know how many millions were siphoned

off by them. Even

Hans Frank, Governor of the

Generalgouvernement,

was found guilty of purloining fur coats, gold bracelets, pens and rings as well as large quantities of food.

Hitler stripped

Frank

of all his Party offices. So much for

Globocnik's "decency and honesty".

The corruption and scandals concerning the SS men, connected with

Aktion Reinhard, were the reason for

the large-scale investigation organised within the SS by SS Judge

Konrad Morgen,

who arrived in

Lublin in

1943. The result of

this investigation was the arrest of several SS men from

Majdanek, including

the commandant of the camp,

Hermann Florstedt.

The prisoners, among them the Polish political prisoner

Jerzy Kwiatkowski,

had seen how

Florstedt and others often stole Jewish property:

"

SS men are looking for valuables. Apart from rummaging through the clothes and suitcases,

they unstitch the pillows, in which Schutzhaftlagerführer Thumann

finds diamonds and other precious stones. And Rapportführer Kostial

and other SS men are digging personally with spades in the Rosengarten

(Rose Garden), where the Jews spend the first night, or where during the day they wait in the queue for the

gas chambers or the bath. The SS are finding whole handfuls of rings, diamonds, gold, US Dollars and Russian

Roubles there."

The corruption affair at

Majdanek resulted in the death sentence for

Florstedt. In

1945, he was executed in

either the

Buchenwald or

Leitmeritz

concentration camp.

Morgen investigated 800 cases of corruption and murder, with

200 resulting in sentences. Amongst others executed was another sometime commandant of

Majdanek,

Karl Koch.

Hermann Hackmann, who had been in charge of protective custody at

Majdanek, was initially condemned to death, but instead was posted to a penal unit.

It should be stressed that

Morgen was in no way concerned with the acts of

murder and robbery carried out in the name of

Aktion Reinhard; these crimes were not only "legal", but also

essential. Rather, it was the "illegal" crimes, carried out for personal gratification or self-enrichment that

concerned him. Nothing better illustrates the absurd dichotomy inherent in Nazism than this spectacle of isolated

cases of murder being investigated in places where thousands were murdered daily. In any event,

Himmler became nervous about where

Morgen's

probing was leading. In

April 1944,

Morgen

was ordered to confine himself to the

Koch case. All other investigations

were stopped.

The end of

Aktion Reinhard did not signify the cessation of the murder and exploitation of the Jews.

Indeed,

Auschwitz-Birkenau was about to enter its most lethal and lucrative phase.

Jews continued to work as slave labourers in the

Lodz Ghetto until its

liquidation in

August 1944, and at many other labour

and concentration camps until the war's end. Under

Albert Speer,

who utilised millions of slave labourers for the purpose, armaments production soared to new

heights in

1944 - 45. But the killing and thievery never stopped.

The real economic value of

Aktion Reinhard is impossible to calculate. Large amounts of money

and valuables never found their way into the hands of the murderers. Tens of thousands of Jews

died en route to the camps, or were shot on arrival, and were buried in their clothes.

Abraham Krzepicki recounted how, on being instructed to

clear the

Schlauch at

Treblinka (the path leading to the gas chambers),

his group of workers

found "a veritable windfall of banknotes which people had torn up and thrown away before they

died." Papers which the Germans considered of no value, such as life insurance policies and share

certificates were burned in the

Lazarett, together with letters, photographs and other personal effects.

The worth of such items is unknown, and unknowable.

In the final analysis,

Globocnik's report was merely the tip of a

gigantic iceberg. How much of the plunder found its way into the vaults of Swiss Banks from

Nazi government and personal sources, can never be calculated.

Stangl

had no doubt that the economic implications of

Aktion Reinhard were of primary importance:

"

Have you any idea of the fantastic sums that were involved?" he asked

Gitta Sereny rhetorically. "

That's how the steel

in Sweden was bought."

Even the economies of neutral countries had benefited. The extent to which the looting fuelled the

post-war West German

Wirtschaftswunder (Economic Miracle) is a matter for speculation.

Certainly, major German banks and industries had profited handsomely from the annihilation

of the Jews. Poles, Ukrainians, Byelorussians and others moved into vacated Jewish premises.

They remain there in safety, for the Jews will never return. The value of property simply destroyed,

either by the Jews themselves in the face of death or by the Nazis and their collaborators, is incalculable.

Add to this the value of tens of thousands of slave labourers, working at little or no cost to their masters,

and the immensity of the larceny becomes apparent.

Yet there is another dimension to this tragedy. For how is it possible to quantify the value of

2 million lives cut short? Some victims were middle-aged, most in the prime of life.

Perhaps 500,000 of them were children. If a single life is priceless, how can a value be

placed on so many lives? For the Nazis not only stole the accumulated wealth of generations

and annihilated a society and a culture which had flourished for 500 years - they destroyed

that society's future capacity to earn, produce, create and expand. In laying waste to the past,

they also succeeded in obliterating the future. That is what was lost, and that is the true economic cost of

Aktion Reinhard.

Sources:

1) Hilberg, Raul.

The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003

2) Arad, Yitzhak.

Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka - The Operation Reinhard Death Camps,

Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1987

3) Gutman, Israel, ed.

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990

4) Padfield. Peter.

Himmler – Reichsführer-SS, Macmillan Publishers Limited, London, 1991

5) Höhne Heinz.

The Order Of The Death's Head, Pan Books Limited, London, 1972

6) Gutman Yisrael and Berenbaum Michael, eds.

Anatomy Of The Auschwitz Death Camp, Indiana

University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1994

7) Epstein Eric Joseph and Rosen.

Dictionary Of The Holocaust, Greenwood Press, Westport

Connecticut and London, 1997

8) Gutman Yisrael.

The Jews Of Warsaw 1939-1943, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1989

9) Burleigh Michael.

The Third Reich – A New History, Pan Macmillan Limited, London 2001

10) Arad Yitzhak, Gutman Israel and Margaliot Abraham, eds.

Documents On The Holocaust,

University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 1999

11) Gilbert Martin.

The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy, William Collins Sons & Co. Limited, London, 1986

12) Donat Alexander, ed.

The Death Camp Treblinka, Holocaust Library, New York, 1979

13) Sereny Gitta.

Into That Darkness – From Mercy Killing To Mass Murder, Random House UK Limited, 1995

14) Reder Rudolf.

Belzec, Fundacja Judaica w Krakowie, Krakow,1999

15) Blatt Thomas Toivi.

From The Ashes Of Sobibor, Northwestern University Press, Evanston Illinois,1997

16) Glazar Richard.

Trap With A Green Fence, Northwestern University Press, Evanston Illinois, 1999

17) Willenberg Samuel.

Revolt In Treblinka, Zydowski Instytut Historyczny, Warsaw 1992

18) Goldhagen Daniel Jonah.

Hitler's Willing Executioners, Little, Brown and Company, London, 1996

19) Kwiatkowski Jerzy.

485 dni na Majdanku, Wydawnictwo Lubelskie, Lublin 1966.

20) Archive of the State Museum Majdanek in Lublin.

Jewish memoirs and testimonies.

21) Archive of the Jewish Historical Institute.

Collection of the testimonies by Holocaust survivors.