|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ghettos |

|

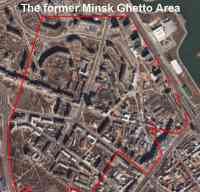

| Minsk Ghetto #1 |

|

| Minsk Ghetto #2 |

By 22 June 1941 and the outbreak of hostilities between Germany and the Soviet Union, the Jewish population of Minsk has been estimated to have risen to 90,000. The increase was largely as a consequence of the arrival of those fleeing eastwards following the German occupation of Poland in 1939. The city fell to the German invaders on 28 June 1941. Within hours of the German occupation, 40,000 men and boys between the ages of fifteen and forty-five were assembled for "registration", under penalty of death; they were Jews, Soviet POWs and non-Jewish civilians. For four days they were kept in a field, surrounded by machine guns and floodlights. On the fifth day, all Jewish members of the intelligentsia were ordered to step forward. 2,000 men did so, believing that the group was to be granted some privileged position. They were promptly marched off to a nearby wood and shot: it was a foretaste of things to come. On 8 July, the Germans killed 100 Jews, and thereafter the murder of Jews by the Germans, singly or in groups, became a daily event.

|

| Minsk Sites |

|

| The Judenrat Building * |

|

| Himmler visiting a POW Camp * |

A few days after the experiment with dynamite, Nebe and Albert Widmann of the Kriminaltechnisches Institut (Criminal Police Technological Institute) tried out another killing method in Mogilev.

The exhaust fumes from two cars were introduced into a sealed room in which 20 - 30 mental patients had been placed. Within a few minutes, carbon monoxide gas killed all of them. This process was not entirely new; the use of bottled carbon monoxide gas to murder the physically and mentally disabled under the auspices of the T4 programme had been in place in the Reich since October 1939. A mobile version under the command of Herbert Lange, in effect a gas chamber on wheels, had been in operation in Western Poland since about the same time. But providing large quantities of bottled carbon monoxide presented problems. It was both expensive and cumbersome.

Nebe came up with the idea of combining the two processes, thus creating the self-sufficient gassing van, in which the exhaust fumes of the vanís engine were re-directed into the sealed rear compartment of the vehicle. He discussed the technical aspects with Walter Hess of the Kriminaltechnisches Institut. The idea was placed before Reinhardt Heydrich, who accepted it.

At about the same time Walter Rauff, in charge of technical matters as head of department IID of the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt - Reich Security Main Office), summoned Friedrich Pradel, head of the transportation service. Rauff instructed Pradel to investigate the possibilities of adapting heavy trucks for gassing purposes. From these various deliberations three types of vans were designed for mass killing; the small Diamond and Opel Blitz, which had a capacity of 80 - 100 persons, and the larger Magirus or Saurer, into which 150 people could be packed.

|

| A Transport from Vienna * |

With effect from 15 September 1941, all German Jews over the age of 6 were ordered to wear the yellow Star of David. On 23 October, Heinrich Müller, the head of the Gestapo, issued a decree authorised by Himmler prohibiting the emigration of Jews from countries under German control.

These two decrees are considered by many historians to be significant evidence that the decision to implement the "Final Solution" had been taken. On 8 November Lange informed Lohse that 25,000 Jews from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were to be deported to Minsk.

In order to make room for them in the ghetto, 12,000 Jews had been slaughtered near the village of Tuchinki on 7 November. Three days later the first 1,000 German Jews from Hamburg arrived in Minsk, to be followed within days by more than 6,000 deportees from Frankfurt am Main, Bremen and the Rheinland. On 18 November a train arrived from Berlin. Subsequent transports brought Jews from Vienna, Brno and other cities in the Reich and the Protectorate.

On arrival in Minsk many of the deportees were taken to nearby woods and shot. The remainder were housed in a separate ghetto known as Ghetto Hamburg, which adjoined the main Minsk ghetto. Above the entrance to this separate ghetto was a sign: Sonderghetto (Special Ghetto). Every night the Gestapo would murder 70-80 of the new arrivals. The ghetto of the Reich Jews was divided into five sections, according to the places from which they came: Hamburg, Berlin, the Rheinland, Bremen and Vienna.

There was little contact between the main Minsk Ghetto and the Reich Ghetto. The Jews from the Reich were to be killed in the major "actions" of 28-31 July 1942, on 8 March 1943, and in the autumn of 1943 on liquidation of the ghetto. Some were sent to Budzyn labour camp near Lublin. Between November 1941 and October 1942, a total of 35,442 Jews from the Reich and the "Protectorate" were deported to Minsk. Only 10 Reich Jews were still alive in Minsk when the city was liberated. Of the 999 Austrian Jews deported to Minsk ghetto, 3 are known to have survived. By the middle of November 1941, Einsatzgruppe B could report having carried out a total of 45,467 executions. On 20 November there was another major Aktion in which a further 7,000 Jews perished at Tuchinki.

|

| Forced Labour in Minsk * |

Another large scale Aktion occurred on 2 March 1942, claiming at least a further 5,000 victims. It was timed to coincide with the Jewish festival of Purim, a story recounted in the Biblical book of Esther. Amongst those killed in this Aktion was a group of children from the Shpalerna Street orphanage. They were taken to Ratomskaya Street and thrown alive into a deep pit that had been dug there. Kube arrived and threw handfuls of sweets to the terrified children. All were killed. When the forced labourers returned to the ghetto that evening, they were ordered to lie down in the snow. A selection was made. Some were taken to the pit in Ratomskaya Street, others to the Dzerzhinsk (Koidanovo) forest. All those selected were shot. Further smaller "actions" continued to occur throughout April 1942.

At the beginning of 1942, Karl Gebl and Erich Gnewuch delivered two gas vans to Minsk. Eventually there were to be four such vehicles operating in the Minsk area. Einsatzkommandos "7b", "8" and "9" each had its own van. The fourth was probably stationed in Minsk itself. Murder of Jews in the gas vans commenced. On 7-8 May 1942 a camp was opened at Maly Trostinec, 12 km east of Minsk, solely for the purpose of extermination. Myshkin, the head of the Judenrat, who had co-operated with the underground, was betrayed in February 1942, arrested and hanged.

Himmler wrote to Gottlob Berger, chief of the SS main office on 28 July 1942, "The Occupied Eastern Territories are to become free of Jews." On that same day, a major Aktion commenced in Minsk, at the conclusion of which, four days later, 30,000 Jews had been slaughtered. The new Judenrat chairman, Moshe Yaffe, was ordered to address the assembled Jews in Yubileiny Square in order to allay their suspicions. At first he began to calm the frantic crowd, but when gas vans drove into the square, he cried out, "Jews, the bloody murderers have deceived you -- flee for your lives!" Pandemonium broke out. Yaffe and the ghetto police chief were among the victims of this Aktion, as were 48 doctors, the leading specialists of Byelorussia. The Judenrat ceased to exist. On the last day of the Aktion, a transport of about 1,000 Jews from Terezin (Theresienstadt) arrived in Minsk and was diverted to Baranovichi, where two gas vans were waiting to kill the deportees. By 1 August 1942 there were officially 8,794 people left alive in the ghetto.

Earlier there had been an intercession on behalf of the Reich Jews from an unexpected quarter. On 16 December 1941, Kube wrote to Lohse. Whilst unconcerned about the fate of the Polish and Byelorussian Jews, Kube stated that the Reich Jews included war veterans, holders of the Iron Cross, those wounded in war, half-Aryans, and even three-quarter Aryans. Although Kube claimed that he did not lack hardness and was ready to contribute to the solution of the Jewish problem, people who come from the same cultural circles as Lohse and himself were different from the brutish local hordes. Kubeís letter had no effect on Nazi procedures so far as the Reich Jews were concerned.

On 31 July 1942, Kube wrote to Lohse again. This time he boasted of having murdered 55,000 Jews in Byelorussia in the preceding 10 weeks - including several thousand of the Reich Jews he had been so anxious to save a few months earlier. He went on to express his hope that the Jews of Byelorussia would be completely liquidated as soon as the German Wehrmacht no longer required their labour.

In July 1943, Kube accused Eduard Strauch, commander of the Security Police and SD in White Ruthenia, of a policy of sadistic barbarity following the killing by Strauch of 70 Jews, employed by Kube. Kubeís charges and complaints were clearly not motivated by humanitarian considerations; rather, he felt that these "actions" by the SS and the police were being carried out over his head and therefore that they weakened his authority.

An indignant Strauch submitted a long report to Bach-Zalewski, enumerating Kubeís many failings: he had shaken hands with a Jew who had rescued his car from a burning garage; he had confessed to appreciating the music of Mendelssohn and Offenbach, adding that "beyond a doubt there were artists among the Jews;" he had promised safety to 5,000 German Jews deported to Minsk. Strauch, who was technically a subordinate of Kube, recommended the dismissal of the Generalkommissar on the grounds that "deep down Kube is opposed to our actions against the Jews." Kubeís bizarre behaviour was brought to a conclusion before any measures could be taken against him. On 22 September 1943 he was killed by a bomb planted under his bed by his maid, a Soviet partisan.

|

| Jews from Minsk Ghetto * |

|

| Minsk Ghetto * |

According to Nazi statistics, between the occupation of the city and 1 February 1943, 86,632 Jews had been murdered in Minsk. There had been many SS and Gestapo men who had perpetrated terrible crimes: Richter, Hettenbach, Fichtel, Menschel, Wentske and others. Early in February 1943, two previously unknown Germans appeared in the ghetto. Jews from the nearby town of Slutzk recognized them as Adolf Rübe and his assistant and interpreter, Michelson. Their appearance, said the Slutzk Jews, meant the liquidation of the ghetto. Over the ensuing months, Rübe together with Michelson, the new police chief Bunge and his deputy, Scherner, terrorised the ghetto. Shootings became so commonplace that people were afraid to venture onto the streets. Orphaned children, the elderly and the disabled were systematically annihilated. In May, with most Jewish doctors having been murdered, patients were shot in their hospital beds. Little by little, the population of the ghetto shrank. By the summer of 1943 there were between 6,000-8,000 Jews left in the ghetto.

|

| POW Camp Shirokaya Street 1942 * |

The final liquidation of the Minsk ghetto occurred on 21 October 1943. The remaining 2,000 Jews were rounded up and killed at Maly Trostinec. The Red Army liberated Minsk on 3 July 1944. A handful of Jews who had been in hiding greeted their liberators.

Large numbers of indigenous collaborators were tried and convicted before tribunals of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD and its successors for crimes committed in Minsk. Investigations began during the closing months of the war, lasting well into the 1980ies. Surprisingly, even during Stalin's day, only a minority of defendants received the death penalty; most were sentenced to ten or twenty-five years in a labour camp. Many of these defendants benefited from Khrushchev's amnesty.

Trials also took place in West Germany; some defendants were acquitted, most received moderate sentences. The most severe sentence handed down in a West German court was reserved for Adolf Rübe, a member of the Criminal Police in Minsk, and the man who had so terrorised the ghetto during its final months, who was sentenced to life imprisonment plus 15 years. Rosenberg was condemned to death by the International Military Tribunal at Nürnberg and hanged. Lohse was sentenced to ten years imprisonment, but released because of ill health in 1951. Nebe was implicated in the 20 July 1944 bomb plot to assassinate Hitler and executed by the Nazis. Bach-Zalewski was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1962. Widmann received a sentence of 6 Ĺ years. Rauff escaped to Chile and died there in 1984. Lange was killed in action in 1945. Strauch was condemned to death twice, by a US military tribunal and by a Belgian court. The execution was stayed because of his insanity.

The population of Minsk in 2004 was in excess of 1.7 million. About 30,000 or slightly more than 1.7% were Jewish.

Sources:

1) Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews. Yale University Press, New Haven 2003

2) Gilbert, Martin. The Holocaust. Collins, London 1986

3) Ehrenburg, Ilya and Grossman, Vasily ed. The Black Book. Yad Vashem, New York, 1981

4) Arad, Yitzhak. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka - The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1987

5) Kogon, Eugen; Langbein, Hermann and Rückerl, Adalbert ed. Nazi Mass Murder - A Documentary History of the Use of Poison Gas. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1993

6) Arad, Yitzhak; Gutman, Israel and Margaliot, Abraham ed. Documents On The Holocaust. Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1999

7) The Einsatzgruppen Case - United States v Otto Ohlendorf et al - Nuremberg, 1947

8) Gutman, Israel ed. Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990

9) Epstein, Eric Joseph and Rosen, Philip. Dictionary of the Holocaust. Greenwood Press, Westport Connecticut, 1997

10) Poliakov, Leon. Harvest of Hate: The Nazi Program for the Destruction of the Jews of Europe. Syracuse University Press, 1956.

11) Gilbert, Martin. Atlas of the Holocaust. William Morrow and Company Inc, New York, 1993

12) Buscher, Frank. Investigating Nazi Crimes in Byelorussia: Challenges and Lessons.

muweb.millersville.edu/~holo-con/buscher.html

13) Klee, Ernst; Dreßen, Willi and Riess, Volker. The Good Old Days - The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. Konecky & Konecky, New York, 1991

Photos:

GFH *

Trostenez - Das Vernichtungslager bei Minsk *

© ARC 2005