|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ghettos |

|

| Ghetto and Killing Sites |

The war reached Przemysl on 7 September 1939, when the first bombs struck the city.

The bombing of the town on 8 September set fire to the shopping centre Pasaz Gansa. Many people, Jews and non-Jews, escaped from the city to the East. The Germans entered the town for the first time on 15 September 1939. Repressions and humiliations, aimed at the Jewish population, started almost immediately.

Around 20,000 Jews still lived in Przemysl at that time, including

|

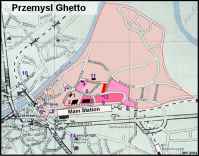

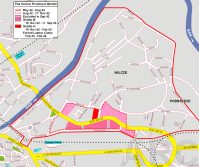

| Ghetto Map |

|

| 1st Mountain Division* |

|

| Ghetto Borders |

Units involved in these killings (the so-called Aktion Tannenberg) were Einsatzkommando I/1 and I/3. Units of the 1st Mountain Division and groups of the HJ (Hitlerjugend) also took an active part in round-ups for forced labour and executions.

"Several days after the arrival of the Germans I was driving along Mickiewicza Street, one of the main thoroughfares in Przemysl, when I saw a ragged line of people running down the middle of the street, all with their hands clasped behind their necks. I pulled over to one side and stopped my truck. Around a hundred people ran past, and as they did I saw that they were Jews. They were half naked and crying out as they ran, "Juden sind Schweine" ("Jews are swines"). Along the line, revolvers in hand, German soldiers were running, young boys about eighteen years old, dressed in dark

|

| Aerial Photo |

I returned home, shaken. Only in the afternoon, when I had calmed down somewhat, did I go out again to return my truck to the power station. Now a new horror met my eyes: distraught, weeping women were running toward the cemetery, for they had heard that all the Jews taken in the morning had been shot in Pikulice, the first village outside town. I put a load of these wailing women in my truck and headed for Pikulice. Right at the edge of the village, beside a small hill, a swarm of people had gathered. I drove up and stopped. What I saw surpassed all belief; it was a scene out of Dante's hell. All the men driven through the streets in the morning lay there dead. Some men from the nearby houses told me what had happened. The Jews had been driven up to the side of the hill and ordered to turn around. A truck was already standing there. A canvas had been lifted off a heavy machine gun, and several bursts of fire rang out, sweeping back and forth. Then a few more shots were fired into the few bodies that were still writhing. All was still. The soldiers climbed into the truck, and drove away. I went quietly up to the little hill. The corpses were lying on their backs or sides in the most contorted positions, some on top of others, with their arms outstretched, their heads shattered by the bullets. Here were pools of blood; there the earth was rust-colored with blood; the grass glistened with blood; blood was drying on the corpses. Women with bloodied hands were hunting through the pile of bodies for their fathers, husbands, sons. A sickish sweet smell pervaded the air. I felt something inside me die, as though my heart had turned to stone. I was choking from the smell, from the sight, from the cries filling the air. I saw everything, but I could not grasp what I saw. Before my eyes I had an image of the laughing young Germans, the proud representatives of Hitler's New Order.”

From: "A private war" by Bruno Shatyn

|

| Demarcation Line in Zasanie |

|

| Burning Temple Synagogue* |

On 27 September the Germans appointed new town authorities in the district of Zasanie.

According to the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact the Germans left the part of Przemysl on the east bank of the river San on 28 September 1939. Before their withdrawal the Germans burned down the Old Synagogue, the Klois (hassidic prayer house), the Tempel Synagogue (progressive synagogue) on Jagiellonska Street and a part of the Jewish quarter.

|

| Russian Border in 1941 |

Under Soviet rule, in April and May 1940, approximately 7,000 Jews were deported from Soviet occupied Przemysl to the Soviet interior, mostly refugees from the West. The living conditions of the Jewish population of the town deteriorated rapidly. Jewish community institutions, factories and shops (only 10% of which were owned by non-Jews) ceased to operate, and their assets were nationalized. All raw materials and merchandise were seized by the new government. Artisans were forced to "voluntarily" enter cooperatives. All privately owned houses were transferred to the city administration.

Prior to the German invasion of the Soviet Union the Jewish population of Przemysl had been almost completely impoverished.

|

| Forced Labour in Zasanie* |

|

| Forced Jewish Pupils |

On 27 June 1940 Deutsch-Przemysl was officially established. It included the areas of Zasanie, Ostrow, Kunkowce, Buszkowce, Buszkowiczki, Zurawica, Walawa, Przekopana Polnocna, and parts of Ujkowice and Bolestraszyce. In spring 1940 a Judenrat was established in Zasanie. This was probably the only Judenrat in occupied Poland headed by a woman, Anna Feingold.

Once more the Jews were rounded up for forced labour and restrictions were introduced as elsewhere in the Generalgouvernement, including the wearing of the white armlet with the Star of David, a curfew from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m., etc. The Zasanie synagogue was turned into a power plant.

|

| Dr Ignatz Duldig |

|

| Early Occupation, forced Jews on Franciszkanska Street |

When the Germans reoccupied Przemysl on 28 June 1941, some 16,500 Jews (25% of the population) lived there.

On their own initiative, the Jews established a committee to represent themselves, headed by Dr Ignatz Duldig. Within a few days the Gestapo arrived and enforced anti-Jewish measures. All restrictions were also extended to Galicia and East-Przemysl, followed by registration of all Jews and the establishment of a Jewish Council (Judenrat) under Duldig.

The Nazis immediately began rounding up Jews for forced labour. Jewish high school pupils were forced to clean the streets, load garbage onto carts and pull them through the streets. Everywhere posters appeared describing the Jews as germs and lice.

In August 1941, Galicia with its capital Lwow was incorporated into the Generalgouvernement. The divided town of Przemysl was administratively reunited under its former name. Jointly with the surrounding municipalities it now formed the "Kreishauptmannschaft (main district) Przemysl" in the district of Krakow. Przemysl was the headquarters of the district chief and thereby became the administrative centre. The district chief was Dr Heinisch until the summer of 1942. He was succeeded by a lawyer, Paul. Their deputy was Dr Herbig.

Przemysl attained special significance as an important supply base for the "German Army Group South", with a number of army enterprises, and important railway junction. The following police units were stationed in the town:

The Grenzpolizeikommissariat (GPK) Przemysl, a department of the security police (Sicherheitspolizei - Sipo) and a detective police department under the SS-Untersturmführer Weichelt. The premises of these three departments were separated from each other, but were under the unified command of the commander of the security police and the SD in Krakow. Furthermore Przemysl became headquarters of the gendarmerie (Gendarmeriezug Przemysl) under captain Haasler with one platoon commanded by the gendarmerie district leader, 2nd lieutenant Pferr, as well as that of a police squad under 1st lieutenant Schaller of the security police. Security police and gendarmerie, which were under the command of the regular police (Ordnungspolizei - Orpo), utilized Polish and Ukrainian helpers. At times, members of the German regular police were also stationed in Przemysl, i.e. in summer 1942, one company of Police Battalion 307.

|

| Gestapo Headquarters |

In charge of this GPK Przemysl department were, until May 1941, the detective senior secretary Friedrich Preuss, then until autumn 1942, the SS-Untersturmführer Adolf Benthin, who was replaced in turn by SS-Sturmscharführer Rudolf Heinrich Bennewitz (who earlier served in Zakopane as SS-Hauptscharführer). He remained head of the department until early 1944. He was followed by SS-Hauptsturmführer Weichelt, who kept this position until the dissolution of the department in July 1944. The deputy of the department head (under Adolf Benthin) was Walter Stegemann.

Within the department three sections existed: the so-called "general" or "political" section (III A), the "resistance" section (Widerstandsbekämpfung - III B) and the "counterintelligence" section (Spionageabwehr - III C). Since from summer 1941, the political section had to deal with all "political matters" in connection with the Jewish population in Przemysl, in colloquial language it was called Judenreferat (Jews section). The GPK was the competent authority for the surveillance of the Jews in Przemysl, whereas the economic administration of the Jews was still in the hands of the district authority (Kreishauptmannschaft). In addition, the Jewish section at the GPK (in particular under SS-Sturmscharführer Richard Timme) was also responsible for Jewish matters. Due to the haphazard distribution of affairs, members of other sections were also occupied with these tasks.

|

| Not Allowed Using a Bridge |

In late autumn 1941, the town quarter of Garbarze was proclaimed as a Jewish residential area. It was bordered in the west, north and east by the bend of the San River and in the south by the railway route Lwow - Krakow.

The establishment of this Jewish quarter took until the summer 1942. Up to this time, Jews were allowed to walk freely through the streets, but with their armbands on. Only the passage to Zasanie via the provisional bridge was prohibited for the Jews.

In winter, the Jews were forced to hand over their valuables and various household goods. Those who did not comply with the Nazi decrees were beaten and imprisoned. On 26 December 1941 Schutzpolizei (Schupo), along with Volkdeutsche (ethnic Germans) and Polish policemen, entered Jewish homes and seized furs and other clothing. Schupo officers started to remove any furs and fur collars from the coats of all Jewish men and women they came across in the streets. They also removed winter boots, mainly from women, and left people barefoot in the street. Jews had to hand over most of their property.

|

| Kazimierzowska 15 July 1942* |

The Germans, including the local Germans (Volksdeutsche), entered Jewish houses and removed furniture, pianos, carpets, silverware and china. Jews sold their belongings because they knew that they would otherwise be forced to hand over everything without compensation. The German response to any kind of "transgression" by a Jew was extremely severe. For example, for wearing the armband on the right arm instead of the left, or visiting the market during prohibited hours, Jews were severely beaten and imprisoned for lengthy periods or were sent to the central prison at Rokitnianska Street, where they were killed.

From spring 1942, consecutive shootings of groups of Jews at the Jewish cemetery at Slowackiego Street began. These shootings were carried out by Gestapo officials in charge of Jewish affairs (Judensachbearbeiter), but also by members of the GPK.

Finally all Jews were forced to move into the ghetto. In addition, Jews from villages in the vicinity of Przemysl continuously poured into the ghetto. By the summer of 1942, around 5,000 Jews from Bircza, Krzywcza, Nizankowice and Dynow had been brought to Przemysl.

In summer 1942, in Przemysl as in all of the larger towns in the Krakow district, the systematic extermination of Jews began. The "evacuations" (Aussiedlungen) were supervised by Polizeiführer Julian Scherner in Krakow. He was responsible solely to the Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer Ost, Heinrich Himmler's deputy in the Generalgouvernement. Scherner had absolute authority to issue directives to the GPK Przemysl regarding the "evacuations". The local supervision and execution of the deportation actions in Przemysl was in the hands of this department.

On 3 June 1942, the Germans murdered all Jewish residents of the Zasanie Ghetto at Dolinskiego Street: 45 people (60 according to some sources) were taken by trucks to the former Austrian Fort VIII Letownia in the Kunkowce suburb and shot.

Between the beginning of June and early July 1942, more and more rumours spread about anti-Jewish riots in Tarnow, Rzeszow and other places. It was difficult to confirm these rumours, and the Judenrat tried to find out the truth, from the Gestapo. The Gestapo confirmed the rumours and promised to preserve the Przemysl Jews from this harsh fate if they "behaved well". Asked by the Judenrat how they could do this, they were told by Gestapo chief Benthin, that if the Judenrat provided him with 1,000 young people for work at the Janowska camp in Lviv (Lwow), they would be safe.

So on 18 June 1942 1,000 young and strong Jewish men were sent to Janowska (later a group of these prisoners was deported from Janowska to the Belzec death camp). On this day the Gestapo shot many of the young men's relatives, who had come to bid them farewell, as well as men who allegedly tried to evade the deportation. Later the Gestapo demanded a large sum for transportation costs...

|

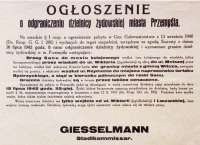

| Official Closing of the Ghetto |

By the time of the closure of the district on 15 July 1942, 22,000-24,000 Jews lived in the ghetto (See the memoires of Aleksandra Mandel)). Only the members of the Jewish council and their families were allowed to remain in their flats outside the residential area until the first deportation in July/August 1942.

On 20 July the Germans demanded 1,300,000 zloty, saying that payment of this sum would guarantee peace and quiet. The same day the "resettlement operation", planned for 27 July 1942, was discussed in the Gestapo headquarters. The participating officers were the county administrator (Kreishauptmann), the municipal administrator, representatives of the order police, the security police, and the head of the Przemysl labour office.

On 23 July 1942, the Gestapo notified the Judenrat that on 27 July (Announcement #1 Announcement #2) there would be an "action" (German: Aktion) which would include most of the ghetto residents.

|

| Life Extension GPK Seal #1 |

|

| Life Extension GPK Seal #2 |

The Gestapo and GPK were unable to manage the Aktion without help from other units: gendarmerie, one company of the regular German Police Battalion 307, "foreign Ethnic German" police (fremdvölkische Polizei), Estonian units of 287th and 288th Police Battalion (recruited from Omakaitse members), SS-units, civilian workers of several departments (especially the district authority), Polish and Ukrainian police and members of the Polish and Ukrainian Baudienst (construction service).

These units, as assistants of the Gestapo, took an active part in the round-ups, as well as the guarding of the Jews, and their mass murder. SS-Hauptsturmführer Martin Fellenz of the SSPF (SS- und Polizeiführer) office in Krakow was responsible for this operation.

The Aktion was carried out on three days: 27 July, 31 July and 3 August 1942. Schutzpolizei and Gestapo units, together with their henchmen, surrounded the ghetto on the first day. 6,500 Jews were deported to Belzec and Duldig and his deputy were shot.

The elderly and handicapped, the sick, and some children (approximately 2,500 people in total) were taken in trucks to the Grochowce forest and other places on the outskirts of the city. There they were shot and buried in mass graves.

On the second day, 3,000 Jews were also deported to Belzec, to be followed on the final day by a further 3,000. At the end of the Aktion, the Jews were forced to hand over a sum of money to the Gestapo, to pay the transportation costs (train fees and provisions for the deportees). The ghetto was reduced in size and the new barbed wire fences around the ghetto borders also had to be paid for by the Jews. By end of August the Gestapo had murdered another 100 Jews in Przemysl.

|

| Max Liedtke* |

|

| Albert Battel |

In mid November 1942, the Jews feared that another Aktion was unavoidable. They started building bunkers. When the second Aktion took place on 18 November (see the decree of 17 November), more than 8,000 Jews without work permits were earmarked for deportation. About 1,500 workers were to be exempted. However, only 3,500 people showed up at the assembly point; the rest of the Jews hid in bunkers. On this day some 500 of the hidden Jews were found and added to the transports destined for Belzec.

|

| Schwammberger |

There was no massive armed resistance in Przemysl. In mid-April 1943 12 young men escaped from the ghetto and tried to join the partisans. They were intercepted by Ukrainians not far from the city and all but one were murdered. The survivor, known only by his surname of Green, was hanged in public shortly thereafter, along with Meir Krebs, who on 10 May 1943, had stabbed a Gestapo-man, Karl Friedrich Reisner.

|

| Bennewitz |

One week after the start of the final Aktion the commander of the GPK, Bennewitz, said that all Jews who reported voluntarily could go to a work camp. So 1,580 Jews gave themselves up.

On 11 September 1943, after they had handed over their valuables and undressed themselves, they were shot in the yard of the Judenrat building, in groups of 50. Their corpses were burned during the following days at the same place. This so-called Turnhallen-Aktion (Gymnasium action) was carried out in the centre of the city, 200 meters away from the busy Przemysl railway station.

From September 1943 until April 1944 further deportations to Auschwitz followed. During this entire period the Germans continued to seek Jews in hiding.

On 28 October 1943, the SS sent 100 people from the Przemysl ghetto to Szebnie.

Between 11 September 1943 and the end of April 1944, 1,000 people, still hiding out in "bunkers", were killed by Gestapo, SS, and the camp commander SS-Unterscharführer Schwammberger.

The camp was destroyed at the end of February 1944, which meant that in theory there should not have been any Jews remaining in Przemysl. But in fact there were still some remaining "bunkers" in the town andits surroundings containing around 120 hidden Jews. From March to June 1944, three or four "bunkers", housing 40-50 Jews, were destroyed. The last hiding place was discovered in May in Tarnawce near Przemysl where 27 Jews were shot. The Kurpiel family, who helped them, were executed in Lipowica.

In early July 1944, the front was rapidly approaching Przemysl. On 23 July, the town was bombed by Russian airplanes. On 27 July 1944, the Russians captured the town, on the exact anniversary of the first Aktion two years earlier.

Immediately after the liberation of Przemysl, the few survivors left their hiding places. At first there were some 100 people in all, but during the next days the number of survivors grew to a maximum of 250. It is estimated that only 400 Przemysl Jews survived the Holocaust in Przemysl itself, Russia, Poland and in other countries.

After escaping to Argentina at the war's end, Schwammberger was extradited to Germany in 1990, where he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

He died in prison hospital on 4 December 2004, the last Nazi war criminal to be tried in Germany.

Trials:

Bennewitz, Rudolf Heinrich: Proceeding suspended because defendant’s ill health - Stuttgart 1963. Bennewitz died 8 years later;

Benesch, Ernst: 6½ years - Hamburg 1980, 1981, BGH 1983;

Fellenz, Martin: 7 years - Kiel 1966, Flensburg 1963, BGH 1963;

Reisner, Karl Friedrich: Life imprisonment - Hamburg 1969;

Schwerhoff, Hubert: Death sentence - Berlin (DDR) 1972;

Schröder, Ludwig: Acquittal - Hamburg 1969, 1981;

Stegemann, Walter Ludwig: Acquittal - Hamburg 1969; re-indicted and convicted to 6 years imprisonment (proceeding suspended), Hamburg 1980, 1981, BGH 1983;

Schwammberger, Josef: Life imprisonment - Stuttgart 1992.

The Przemysl Album

Sources:

1. Sefer Przemysl, Tel Aviv 1964;

2. Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust;

3. Relacje collection from Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw;

4. Indictment against Stegemann, Benesch, Brand and Schröder at the Hamburg Provincial Court, 1979;

5. Aaron Freiwald and Martin Mendelsohn: The Last Nazi, W.W.Norton & Co., New York 1994.

Photos:

Yad Vashem *

USHMM *

GFH *

Muzeum Ziemi Przemyskiej *

© ARC (http://www.deathcamps.org) 2005